This is how we roll... backgammon dice

Backgammon is one of the oldest board games in the world (much older than chess). It is a two-player game, where pieces are moved according to the roll of two dice. If you want to know more about backgammon, Wikipedia article might be a good start.

One of the major questions when playing (online) backgammon is: Are the dice fair and random?

This article will try to answer that question on an example from DailyGammon.

DailyGammon (DG) is a free website for online turn-based backgammon playing, or to quote their own words: DailyGammon is postal chess meets backgammon meets the internet.

Dice rolls on DG are created with a help of the famous random.org, which has been proven to be a true random generator (compared to pseudo-random generators) in various statistical analyses. The actual process of creating the dice rolls is explained in DailyGammon’s help, where you can also find the actual Perl script used.

The test I used for testing the randomness of DG dice was Pearson’s chi-squared test. In short, if the test shows P-value of less than 0.05, that means that dice are not behaving randomly; P-values higher than 0.95 would mean that dice are following uniform distribution a bit too closely; if the P-value falls between 0.05 and 0.95, we can say the dice are indeed random.

Data gathering

For this analysis I decided to use the data from my own DG matches. Since joining DG in the summer of 2009, I’ve played 2138 matches.

The first step was to write a small script to download match logs for all those matches. The match log looks like this (just a part of it is shown):

3 point match

Game 1

JHD : 0 miran : 0

1) 62: 24/18 13/11

2) 42: 8/4 6/4 61: 11/5 6/5

3) 51: 13/8 8/7* 33: 25/22 13/10 6/3 6/3

4) 41: 7/3* 4/3 51: 25/20 10/9

The part shown is a start of a first game of a 3 point match (the match lengths on DG vary from 1 point matches to 25 point matches) between a player called JHD and me. I was first on the roll, I have rolled 6-2 and played a 24/18 13/11 move. The next move was from JHD where he rolled 4-2 and played 8/4 6/4. Then I rolled 6-1, he rolled 5-1, etc.

The next step was to extract the dice info from the match logs. Python script was written, which extracted not only the values on the dice, but also the information if it was the first roll of the game (more about the reasons for that a bit later), and who was on roll—me or my opponent.

Some basic stats:

- 2138 matches played, on average 0.80 matches per day,

- 16,294 games, on average 7.62 games per match,

- 606,148 moves in total, or 37.20 moves per game, or 283.51 moves per match.

Data analysis will be divided in two main parts—the analysis of the dice on the first roll of the game, and the analysis of the dice on the other rolls of the game.

First roll

When backgammon is played over the board, every game starts with each player rolling one die and the player who rolled the higher die starts first and plays numbers on those two dice (his and opponent’s). If both players roll the same number on the dice, they re-roll until one player rolls a higher die. (When playing online, re-rolling happens behind the scenes.)

The important thing to notice here is there are no doubles (the same number on both dice) on the first roll.

If the dice are fair, each player should be the first on roll 50% of time in the long run. The key words here are the long run, meaning it could happen (and it happens) that one player will start 10 or more times in the row first, but in the long run the things will balance out.

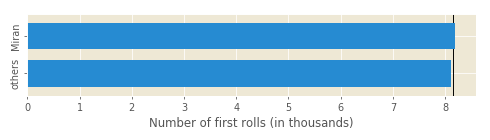

In Figure 1 we can see the number of times each player has been the first on roll, and the black vertical line is the expected value:

Out of 16 thousand games, I’ve started first 68 times more than my opponents. Does that mean the dice are favouring me? Chi-squared test dismisses that possibility—chi squared value is 0.284, and for one degree of freedom this gives a P-value of 0.594—meaning this discrepancy in the number of first rolls for each player is quite expected.

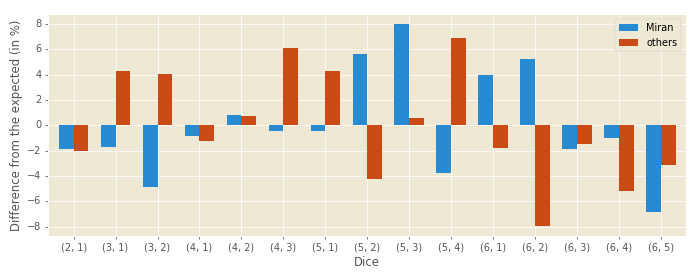

Next thing to check is to see if DG favours some rolls on the first roll over the others. The distribution of the dice combinations on the first roll is shown in Figure 2:

We can see that the most rolls containing a 6 appear less frequently than expected, with 6-5 roll appearing 5% less than it should, while the most rolls containing a 3 appear more frequently than expected, with 5-3 roll appearing 4.3% more than it should.

Chi squared value is 8.734, and for 14 degrees of freedom (15 different rolls, minus one) this gives a P-value of 0.848—a relatively high value, meaning these kind of differences are quite normal for an uniform distribution and this number of observed rolls. In other words, the long run here isn’t long enough.

The last thing to check for the first rolls is to see if the dice distribution is different depending on who is on the roll, me or my opponents.

The distribution of rolls for each player (or to put it more precisely—the difference from the expected number of rolls) is shown in Figure 3, and experienced backgammon players will probably like to check the distribution of the five best opening rolls: 3-1, 4-2, 6-1, 6-5, and 5-3, respectively.

5-3 seems to be my favourite first roll, with 6-5 being the least favourite. The largest discrepancies between me and my opponents seem to be with rolls containing a 2, but once again chi squared test dismisses a possibility of some intentional favouritism (P-values of 0.4175 and 0.5367).

Other rolls

On other rolls the doubles (the same value on both dice) are possible, and the doubles in backgammon are especially powerful. While the probability of rolling a certain double (let’s say 5-5) has half the probability of rolling a non-double (let’s say 4-3: it can be rolled as 4-3 (four on the first die, three on the second die) and as 3-4 (three on the first die, four on the second die)), doubles in backgammon are played twice—the roll of 5-5 is played like there were four dice with 5’s on them: 5-5-5-5.

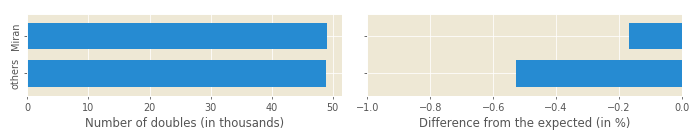

There are six possible doubles (from 1-1 to 6-6) out of 36 different rolls (6x6, two dice with six numbers on each), meaning the doubles should be rolled 1/6 of the time. Figure 4 shows if it is really like that:

While some players are influenced by confirmation bias and are sure that doubles come more often than they should (and usually for their opponents, and especially when it is favourable for their opponents), we can see that doubles on DG come less frequently than expected. Is it possible for a random dice generator to be this wrong after around 590,000 rolls? Chi-squared tests finds this is nothing to write home about, with P-value of 0.221.

I’m getting more doubles than my opponents. Should they worry they’re being cheated? The difference in the number of doubles between us is rather small and the test confirms that: P-value is 0.878.

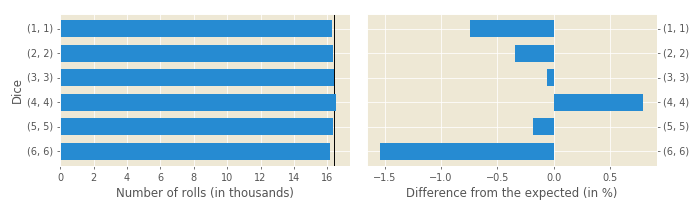

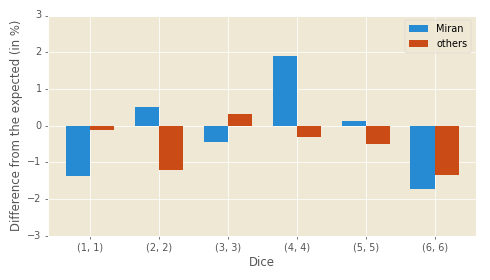

Another thing to check is to see if any of six doubles is more (or less) frequent than the other doubles. This is shown in Figure 5:

Double 4’s are the only double coming up more frequently than the expected value of 1/36th of all rolls. The best racing roll, 6-6 (remember, played as four 6’s) is the least common double. These differences seem to be quite common for the expected uniform distribution, with P-value of 0.427.

We’ve already seen that I’m getting a bit more doubles than my opponents, but how are they distributed between me and them for each double? See Figure 6:

It seems my rolls are responsible for that spike in double fours and the lack of double ones seen in the previous figure. Should my opponents try to compensate for that “lack of randomness”? Chi-squared test, with P-value of 0.889, thinks this is quite random.

Non-doubles

The largest analysed group of dice are the non-double rolls on other-than-first roll. There are almost half a million of them. With that large amount of observed samples, we expect to see the distribution that closely follows the expected uniform distribution (every roll is equally likely).

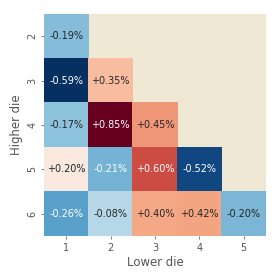

Comparison between observed and expected rolls can be seen in the heatmap in Figure 7:

The largest discrepancy is for 4-2 roll, which happens 0.85% more than expected, followed by 5-3 roll with +0.60%. The least common rolls are 3-1 and 5-4, which happen 0.59% and 0.52% less than expected, respectively.

Looking at the (colours of the) heatmap, one could say that 3’s are the most common roll, and 1’s are the least common. P-value of 0.870 suggests this is quite ordinary.

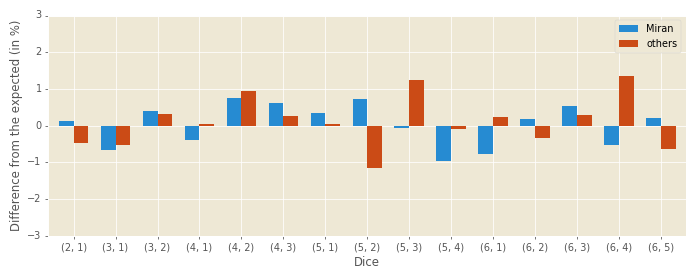

Finally, we’ll compare the non-doubles distribution for each player. See Figure 8:

In the above figure we can see that my opponents have some rolls (5-2, 5-3, 6-4) which differ more than 1% from the expected values, but the chi-squared test says this is normal (P-value 0.658). More concerning are my close-to-perfect rolls with the P-value of 0.920—but this is still in the normal territory.

Conclusion

While it would be more thrilling to have a bombastic title Online backgammon site cheats its players or similar, (un)fortunately the tests performed here have shown the dice on DailyGammon are fair and square (with rounded corners).

Now that you know there is no cheating going on, all I can do is to invite you to create an account on DailyGammon, and join one of the nicest online communities. If you’re already a member, feel free to invite me for a game or two—my nick is miran.